İlhan Karakılıç on a Samsun exchangee village that wove the yearly cycle of tobacco production and memories of their former home into a counterpoint of continuity and loss.

.

İlhan works in the Department of Sociology at Bahçeşehir University.

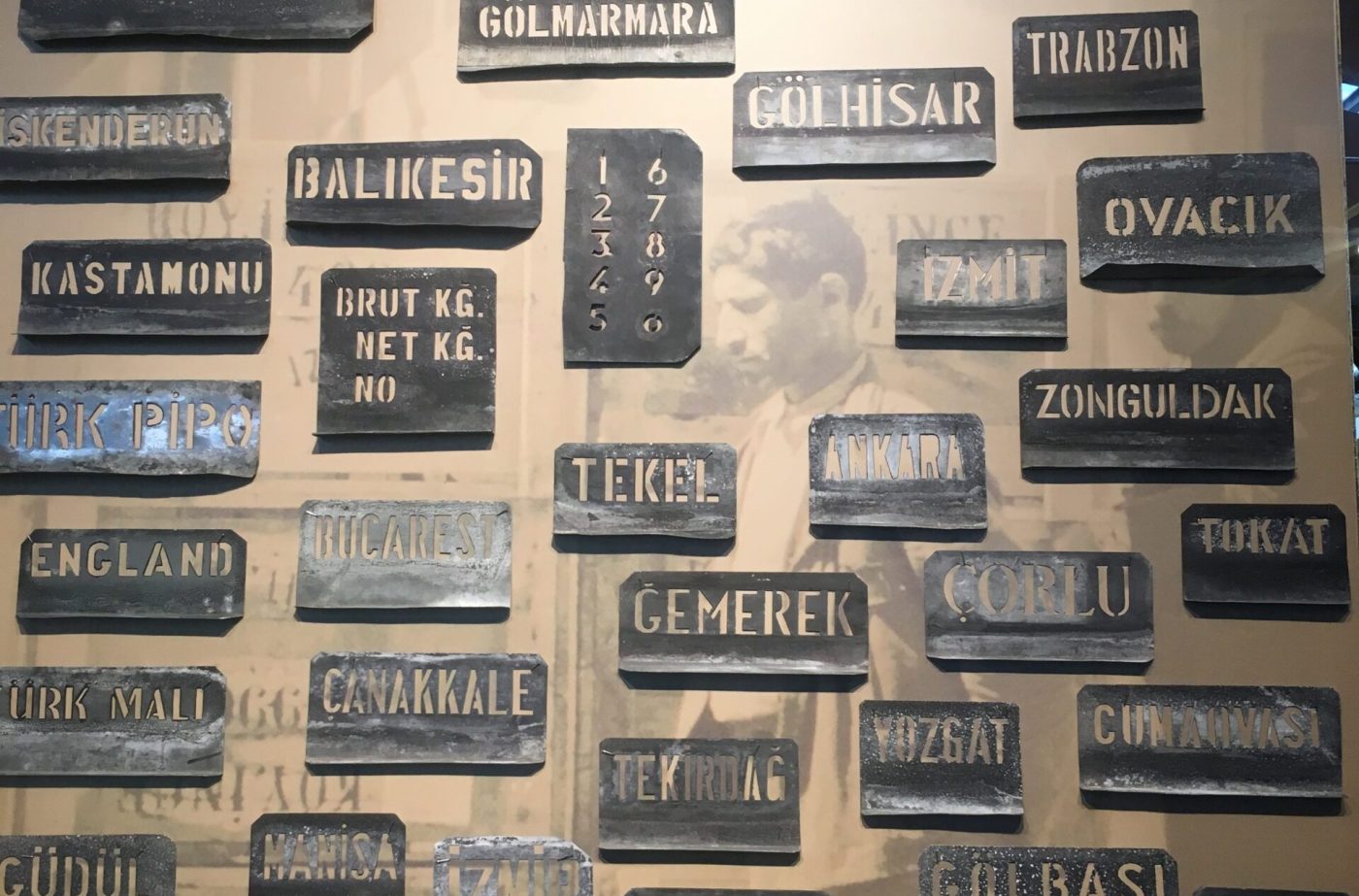

Back in 2011 I was doing fieldwork in the village of Sarıdünya near Samsun, a village whose population was made up of exchangees, displaced by the Lausanne population exchange convention of 1923. [1] To be honest, I was having a hard time. All the conversations I was having, which included semi-structured, in-depth interviews, kept coming back to tobacco production in the village, which had ended two years before. I kept asking about the population exchange, they kept telling me about tobacco.

Tobacco production was nationalized immediately after the establishment of the Turkish Republic, in 1923. As part of a later drive towards import-substitution industrialization (1960-1980), the state integrated many different regions of Anatolia in modern commodity markets, changing cities, towns and villages both economically and socially. Cooperatives were established, factories opened, special seeds and techniques were disseminated, reflecting the importance of tobacco as a source of the foreign currency Turkey needed to finance other industrial initiatives.

The villagers of Sarıdünya found themselves part of this picture as soon as they arrived in Turkey from Greece in 1924. This is why they answered every question I asked about the exchange by drawing the conversation back to tobacco production. Before the population exchange, Sarıdünyalı people produced tobacco in their villages in Greece. Prior to the exchange tobacco had been produced by the Greeks who then lived in Sarıdünya. It was recognized that the area was suitable for tobacco production. Tobacco production became a habitus that connected “before” and “after” (the exchange), old and new hometowns, past and present.

Tobacco production is a year-round, labour-intensive activity that binds together family members, neighbours and acquaintances across the generations. Especially in the summer months, when the tobacco is picked and strung on the ropes for drying, people spend long periods together around piles of tobacco leaves. Practices surrounding tobacco production saw the villagers establish connections with each other and with their land, as well as with the Turkish state and the tobacco market. A villager born in Sarıdünya would experience life as an exchangee tobacco producer, from childhood to old age. As she produced tobacco, she also shaped her identity as an exchangee tobacco producer. The exchangee habitus and these practices created a foundation for the social memory of the population exchange and exchangee identity. In this respect, the exchangee habitus served both as a system of enduring and adaptable dispositions and as a medium where past and present experiences merged, as Bourdieu asserts. [2]

When I asked Cemal, a 67-year-old retired tobacco farmer how he learned about the population exchange, he responded by recounting an incident that occurred while he and his grandmother were stringing tobacco together:

Back then, there were many reasons to ask. For example, we’re tobacco producers, we plant tobacco. My grandmother was a 70-, 80-year-old woman. She used to sit and start singing Rumelian folk songs [murmurs a song]. Rumelian folk songs. Back then, you heard them straight from the mouth.

There’s a meaning in folk songs, as well. They always say meaningful things like that. I used to ask what Didn’t you see my Recep on the banks of the Danube? was. The banks of the Danube, you know, for example, something that comes all the way from our grandfathers, a historical thing. War memories, she used to tell back then. I used to ask her, and there would be a meaning.

We also asked for the folk songs like The Red Rose has a Name, All those who See it Cry. Why would you cry? What does it mean? You tell what happened to you. It’s difficult for you to change it. She’s taken the damage. They started telling as if they were bombs ready to explode. What they’ve seen, how they’ve suffered, what they did. Our adults would tell. We don’t have much other information. That’s it.

This is why every conversation about the exchange became a conversation about tobacco production. However, tobacco production ended in 2011, after the tobacco industry was privatized. In the village nobody produces tobacco anymore. The memory of the exchange has lost a very important pillar: the world of practices through which it is transmitted. In an environment where there are no longer these practices that bring people together, the memory of the exchange began to be carried by villagers with access to cultural products, such as movies, books, memoirs, or who have connections with associations and their activities. These villagers can make their communicative memory into cultural memory, as Assmann understands it, by extending their exchangee habitus with the help of cultural capital they acquired when they migrated to city centers such as Samsun or İstanbul.[3]

For a more detailed discussion, see Ilhan Karakılıç “Social Memory of the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange in Daily Life: a Case Study of a Tobacco-Producing Village in Turkey”, Sociologia Ruralis, 61.1 (2020).

Notes

[1] The name of the village and its residents have been anonymized and changed respectively, to protect confidentiality.

[2] Pierre Bourdieu and Loic J.D. Wacquant, An invitation to reflexive sociology (Oxford: Polity Press, 1992).

[3] J. Assmann, “Communicative and Cultural Memory”, in Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2008).

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.