Jonathan Conlin shares a recent find from the National Archives in Kew: a 1919 memo in which Arnold Toynbee weighs in on the question of whether to “reconvert” the Hagia Sophia into a place of Christian worship.

.

Jon is a convenor and co-founder of TLP.

Context

In March 1919 Arnold Toynbee was thirty years old and working for the British peace delegation in Paris. He had joined the Foreign Office in London in 1917, assigned to the Political Intelligence Department, which would prove to be a forcing house for a number of great historians, including, of course, Toynbee himself. As Erik Goldstein notes, the PID was restructured in October 1918, and Toynbee found himself in the Middle East Section led by Sir Louis Mallet, former ambassador to Constantinople. [1] Although Toynbee’s output in this period was characteristically Stakhanovite, it is striking that he felt the need to sign his name in full at the end of this lengthy note of March 1919, the full text of which is given below. [2] As a docket moved around an office each member of the team made a note on it, recording that they had read both the documents it contained as well as their colleagues’ comments. Most signed using their initials. The fact that this comment is signed “A. J. Toynbee”, rather than simply “A.J.T.” is revealing – but of what? Perhaps Toynbee felt himself to be the “new boy”, whose initials were not yet recognized by colleagues.

The file to which this docket is attached is entitled “Future of San Sophia”. It contains a number of the more important memorials supporting “reconversion” to Christian worship, memorials that had originally been sent to 10 Downing Street, and then forwarded to Paris by the Prime Minister’s Private Secretary. Neighbouring files contain many other similar memorials, both for and against “reconversion”, from across the British Empire and wider Muslim world. Many were organized by dedicated lobby groups, such as the St. Sophia Redemption Committee, led by the Conservative MP Samuel Hoare. Hoare’s memorial was signed by, among others, Toynbee’s father-in-law, the classicist Gilbert Murray. In his comment Toynbee refers to another pro-reconversion memorial from members of the University of Oxford, addressed to David Lloyd George “and the other Representatives of the British Empire at the Peace Conference.” These memorialists were responding to rumours that the “Turkish government” might be permitted to retain Constantinople, and argued that “the Turkish rulers and people” had demonstrated themselves “fundamentally unfit to exercise rule over members of other races and religions.” Turkish “methods of imperial government are entirely alien to the principles of humanity and justice which it is the purpose of the Peace Conference to promote.” The memorialists then jumped to arguing that “the great church of St. Sophia” should be restored “to the use of the Christian Religion and of the Orthodox Eastern Church.” Allowing the building to remain as a mosque was, they opined, “a sign of conquest” and “a symbol of the oppression of the Ancient Churches of the East by the sovereignty of an alien Power.” The majority of the city’s population was, they claimed, “of Greek race.” Noting the dangers of “unwise precipitancy”, however, they recommended that the building be “closed for a time” before rededication.

Toynbee’s comment contains a number of interesting reflections on the potentially destructive symbolic power of great buildings, on “Moslems” and “Osmanlis”, and on the authority of the past as a guide to decision-making. It clearly roused Arthur Hirtzel, Assistant Under-Secretary of the Political Department at the India Office, whose marginalia add a further layer of interest. As Goldstein remarks, there was little love lost between the Foreign Office and the India Office during this period: at one meeting Foreign Secretary Curzon told Hirtzel and a colleague that “Your India Office is really beyond all limits.” Unlike Toynbee, Hirtzel did not feel much need to consider the Empire’s Muslim subjects when addressing Constantinople. [3] Hirtzel disagreed with his Secretary of State, Edwin Montagu, who felt that stripping Turkey of her capital would rouse anti-British feeling among Indian Muslims.

After this unusually long comment the docket passed to Robert Vansittart, who noted that “To take S. Sophia from the Moslems now w[oul]d be gratuitous looking for trouble in its worst form.” Perhaps surprisingly, Hirtzel wrote “I agree” below Vansittart’s comment. While Hirtzel agreed with Toynbee’s conclusions, he challenged the arguments by which they had been reached. This was not a “historical” question for Hirtzel, but a “religious” one. Though “we hear a good deal about Moslem feeling”, it was forgotten that “Christians have their feelings too.” “To the Christian, consecration and desecration are very real things.” At the start of the Great War Hirtzel had remarked that Christians would view the mooted transfer of the calphate to Palestine as “sacrilegious.” As Goldstein and John Fisher have noted, Hirtzel viewed the British Empire as something “given to us as a means to that great end for which Christ came into the world, the redemption of the human race.”[4]

Finally the docket passed to the chief, Mallet. “Keep until question reaches a riper stage”, he wrote. The file was closed. The Hagia Sofia would be “sterilised” by Kemal Atatürk in 1925, becoming a museum. In 2013 the Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey joined calls for its rededication as a mosque. In 2018 President Recep Tayyip Erdogan joined the agitation, but bided his time. The calendars aligned in 2020: 24 July fell on a Friday, and so regular Friday prayers could be resumed on the (97th) anniversary of the Treaty of Lausanne. For some, it has been worth the wait to relish the symbolism, itself based on a radical reinterpretation of Lausanne, as a “defeat” for which Erdogan must seek vengeance. To borrow a phrase from Toynbee, it was a case of “settling the future in reference to the past”.

[1] Erik Goldstein, “British Peace Aims and the Eastern Question: The Political Intelligence Department and the Eastern Committee, 1918”, Middle Eastern Studies 23.4 (1987): 419-436 (420).

[2] “Future of San Sophia”, 28 March 1919. The National Archives, Kew. FO608/111, f. 466 (E5593).

[3] Goldstein, “British Peace Aims”, 429.

[4] John Fisher, “Sir Arthur Hirtzel and the Pax Britannica”, Diplomacy & Statecraft 32.2 (2021): 263-288 (265); Erik Goldstein, “Redeeming Holy Wisdom: Britain and St. Sophia”, in Melanie Hall, ed., Towards World Heritage: International Origins of the Preservation Movement, 1870-1930 (London: Routledge, 2011), pp. 45-62; Goldstein, “Britain’s Plans for a New Eastern Mediterranean Empire, 1916-1923,” in Jonathan Conlin and Ozan Ozavci, eds., They All Made Peace – What Is Peace? The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the New Imperial Order (London: Gingko, 2023), pp.53-75 (57-58).

Text

See also the Oxford memorialists’ arguments. I think the main points in the case are as follows:-

(i) The political severance of C[onstantino]ple from the Ottoman Empire and the reconversion of S. Sophia are entirely separate questions.

(ii) The political loss of C[onstantino]ple is a sufficient visible sign that the Ottoman domination over the Middle East has come to an end.

(iii) If, having removed C[onstantino]ple from under Ottoman sovereignty, we proceed to reconvert S. Sophia, we shall be striking no longer at the Turkish state but at the Moslem population of C[onstantino]ple, which will still form about 50% of the inhabitants of the city. By depriving this population of their principal mosque, we shall be injuring them not as Osmanlis (which they will have ceased to be), but as Moslem citizens of an international state, whom we shall be penalising at the expense of their Xtian [i.e. Christian] fellow-citizens. This will arouse resentment not only among the Turks but all over the Moslem world.

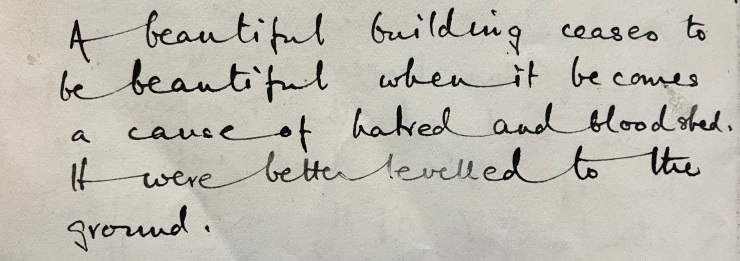

(iv) The sole argument for reconversion is historical, and this is inherently vicious, since it means settling the future not in reference to the future but to the past. [In margin: What about Zionism on this line of argument? AH] Reconversion will inflame religious feeling in the Middle East (with all its catastrophic accompaniments), though it should be the object of the Peace Conference to allay it. For the sake of satisfying the antiquarian sentiment of a few individuals, we shall be planting fresh seeds of massacre in every district in the Middle East where Moslems and Xtians live together. [In margin: This is not a fair description of Sir Samuel Hoare’s Memorial.] A beautiful building ceases to be beautiful when it becomes a cause of hatred and bloodshed [In margin: Did Helen cease to be beautiful?]. It were better levelled to the ground.

A beautiful building ceases to be beautiful when it becomes a cause of hatred and bloodshed. It were better levelled to the ground.

Arnold J. Toynbee

I venture to make the following suggestions for the treatment of the building:-

(a) The mandatory in the Straits should take architectural control of [S. Sophia] as an international monument of Xtian and Islamic civilisation.

(b) Subject to this, it should be left as a mosque under the ecclesiastical control of the local Moslem “millet” in the straits zone (which will presumably be organised as a separate community from the Moslems of Turkey, with a local Sheikh-ul-Islam).

(c) If the Moslem community in C[onstantino]ple eventually dwindles to an inconsiderable fraction of the population, the status of the building should be reconsidered. In this event it might be treated like the Sainte Chapelle at Paris – that is ‘sterilised’ ecclesiastically (on the analogy of the military ‘sterilisation’ of the left bank of the Rhine). In any case, it should not be reconverted into a Church without going through this transition stage for a long period. Interim sterilisation is advocated by the Oxford memorialists, and is a wise suggestion. A. J. Toynbee 30.3.19

IMAGE CREDIT: AGENCE ROL, HAGHIA SOPHIA, 1915.

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.