Burcu Kaleoğlu Uçaner on the lessons we can take from the civics textbooks of early republican Turkey.

.

Burcu is a PhD candidate at Middle East Technical University.

The loss of Balkans and the invasion of remaining Ottoman lands by the Entente powers during the First World War left the non-Muslim element as the most significant ‘other’ of a nascent Turkish national identity. As authoritarian nationalism reached its zenith, the 1930s witnessed a high degree of Turkification under Single Party rule. “Minorities”, as in non-Muslims and non-Turks, faced marginalisation if they failed to meet the basic conditions of becoming a Turk. Civics textbooks are powerful tools by which elites reproduce official ideology, setting boundaries diving insiders and outsiders. Written for primary school students and published between 1930 and 1932, Ali Kami’s civics textbooks afford a useful guide to the othering of Ottoman minorities in the early Republic. [1]

According to these textbooks the most essential requirement is to speak Turkish: “under the Turkish flag, there should not and will not be any language other than Turkish as a family language.” [2] Minorities could be tolerated as Turkish citizens if they adopted Turkish as their mother tongue. The Republic is contrasted with a demonized vision of the late Ottoman world, in which Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians were (as the textbook has it) “Turkish children who did not recognize and love their nation.” This passage deserves to be quoted at length;

On the one hand, the Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians living under Turkish rule and protection, instead of embracing Turkishness and the Turkish language, were reading books in their own languages in their schools. They wanted to give themselves the colour of a nation other than Turkish. These were Turkish children who did not recognize and love their nation. [3]

Here we see different ethnic and religious groups identified as “Turkish children,” albeit ones who are failing to embrace Turkishness by dint of their failure to use the Turkish language. After “our side was defeated in the World War” and Turkish lands invaded by enemies such as the French, English, and above all the Greeks, “the state was ruined. The nation was finished. When the Greeks landed in Izmir, they slaughtered even women and children. They robbed and killed the people.” [4] Eventually, the war was won and “the enemies who could not escape on the ships were thrown into the sea […] The Turkish nation had proved that it was the free master of its free homeland.” [5]

Here Greeks are seen from a state-centric perspective, referred to as “enemies,” not as minorities within the state. “The Greek Prime Minister (Venizelos), who was our arch enemy at the time, was present during the drafting of the Treaty of Sèvres and deceived the Allied powers by saying that he would crush the Anatolian rebels within three weeks” [6] Venizelos is portrayed as such an “arch enemy” that he could apparently deceive other “enemies” and turn them against the “Anatolian rebels,” the future Republican elite.

A few pages later Greeks within the Empire are presented as “local Greeks” described as “helping the enemy”, as in the Hellenic Army, while at Smyrna/Izmir they acted “monstrously”: “They shed blood, beating white-haired old men to death with sticks.” [7] While Armenians, Greeks and the Palace Circle are allegedly “pleased” at the Allied occupation of Istanbul, “benevolent citizens were sorrowful.” [8] The “true owners of the country, the Turks were in captivity.” [9] Thus the Palace Circle, Armenians and Greeks are represented as the significant others of the Turkish national identity. In this textbook the term “enemy” is used 58 times, of which 27 instances refer to Greeks, 17 to “foreign” enemies in general and 12 to the Entente powers, Only once do we find this “enemy” label applied to internal enemies.

Notes

[1] Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 3, (İstanbul: Hilmi Kitaphanesi, 1930), Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 5, (İstanbul: Hilmi Kitaphanesi, 1931-32).

[2] Ibid., 12.

[3] “Bir taraftan Türkün idare ve himayesi altında yaşayan Rumlar, Ermeniler, Bulgarlar, Türklüğü ve Türkçeyi benimseyeceklerine kendi mekteplerinde kendi lisanları ile Türklerin aleyhinde yazılmış kitapları okutmaktan geri kalmıyorlardı. Onlar kendilerine Türkten başka bir millet rengi vermek istiyorlardı. Milletini tanımayan ve sevmeyen Türk yavruları idi”. Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 5, 25-26.

[4] “Devlet mahvolmuş demekti. Milletin işi bitikti. Yunanlılar İzmire çıktıkları vakit kadınları çocukları bile kesip doğradılar. Halkı soydular, öldürdüler”. Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 3, 86, 87.

[5] “Gemilere binip kaçamayan düşmanlar denize döküldü. Türk milletin hür yurdunun hür efendisi olduğunu ispat etmişti”. Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 5, 91.

[6] “[…] Sevr muhadesinin tanzimi sırasında hazır bulunan ve o zaman baş düşmanımız olan Yunan başvekili (Venizelos)Yunan ordusunun üç hafta içinde Anadolu asilerini tepeliyeceğini söyliyerek İtilâf devletlerini kandırmıştı”. Ibid, 39.

[7] “Yunan askeri İzmirde canavarca hareket etti. Kan döktü, can yaktı, ak saçlı ihtiyarları sopalarla döverek öldürdü. Silâh ara- mak behanesile evlere girdi. Ne bulduysa aldı. Kadın erkek nice masum halkın kanına girdi. Bütün bu işlerde yerli Rumlar ön ayak oluyarlardı”. Ali Kami, Yurt Bilgisi 5, 29.

[8] “Bütün hamiyetli vatandaşların boynu büküldü, Rumlar, Ermeniler bir de saray muhiti çok memnundu”. Ibid, 33.

[9] “Memleketin asıl sahibi olan Türkler esir vaziyetinde kaldı”. Ibid, 33.

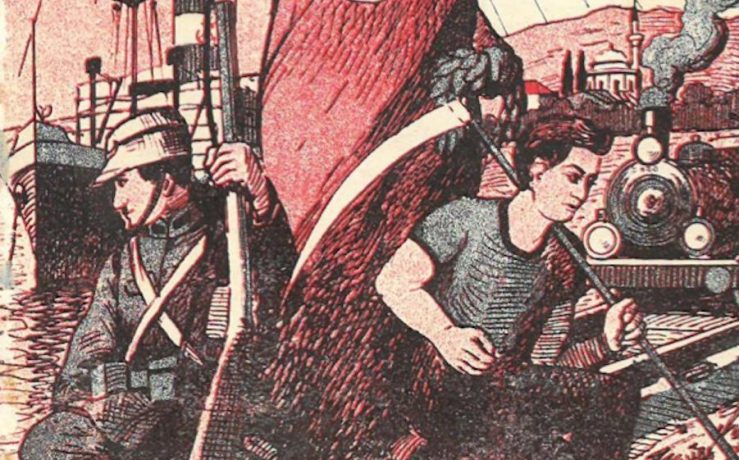

IMAGES: DETAILS FROM THE COVER OF ALi KAMİ, YURT BİLGİSİ 5 (İSTANBUL: HİLMİ KİTAPHANESİ, 1931-32), COURTESY BURCU KALEOĞLU UÇANER

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.