Anna Batzeli reveals how French forces brought cholera to Piraeus during their occupation of Greece, making the war twice as deadly.

Anna is postdoctoral researcher at the Democritus University of Thrace, Greece.

During the Anglo-French occupation of 1854, a devastating cholera outbreak struck Piraeus, spreading rapidly to nearby Athens. This marked the first large-scale health crisis faced by the newly established Kingdom of Greece. Locals referred to the epidemic as “The Foreigner” (i kseni), reflecting their belief that it had been brought by the French occupation troops. The French, who failed to inform Greek authorities about the disease, caused significant delays in implementing containment measures. In less than six months, the outbreak claimed the lives of over 3,000 people, nearly one-tenth of the populations of Athens and Piraeus at the time.

Greece had gained independent statehood in 1830 and was officially recognized as a kingdom in 1832. However, the territorial boundaries of the fledgling kingdom fell short of the aspirations of many Greeks, as large Greek-speaking populations remained under Ottoman rule. The nationalist vision known as the “Great Idea” (Megali Idea), which sought the unification of all Greek-inhabited regions, began to shape the political and military decisions of the Greek state. The Crimean War (1853–1856) between the Russian and Ottoman Empires seemed to provide Greece with an opportunity to realize these territorial ambitions. Greek officials assumed that Russia, as a fellow Orthodox Christian power, would support their claims. Acting on this belief, Greece launched military campaigns against the Ottoman Empire, invading Thessaly and Epirus[1].

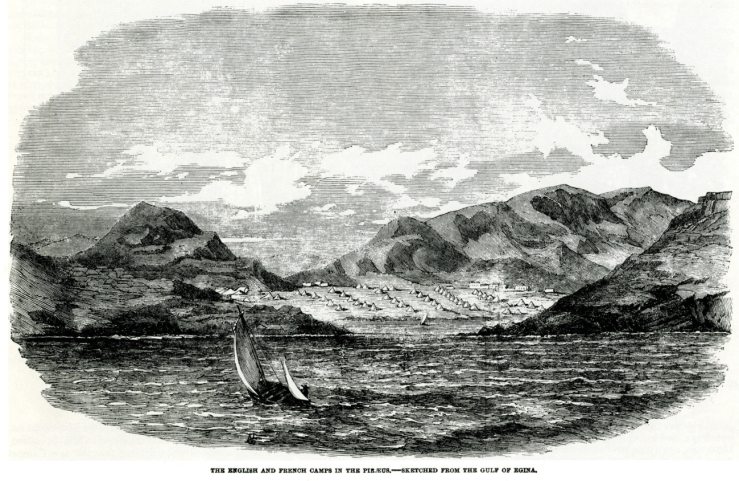

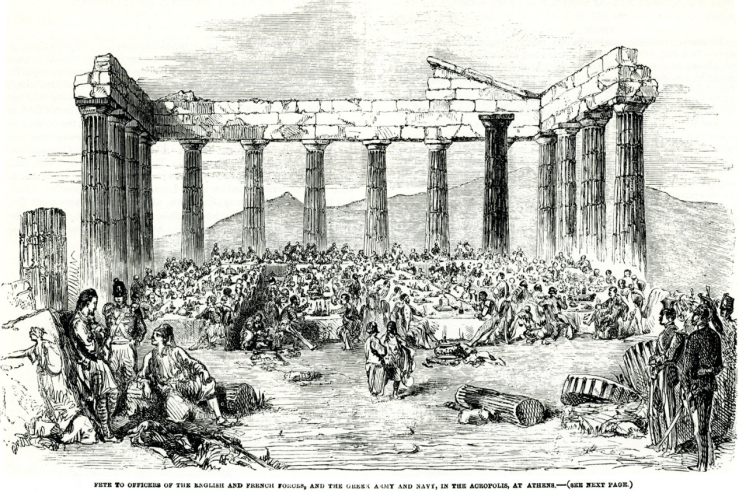

However, the anticipated support from Russia did not materialize. Instead, Greece’s actions provoked Britain and France, who sought to preserve the order in the region.[2] The two powers demanded Greece’s withdrawal from Ottoman territories and, in April 1854, deployed troops to Greece. French and British forces occupied Piraeus, the country’s main port and a critical gateway to Athens, to prevent further hostilities between Greece and the Ottoman Empire. [3]

While the occupation succeeded in averting a broader conflict, it had devastating unintended consequences. Cholera, a deadly disease that had already swept through parts of Europe, arrived with the French forces. Primary sources suggest that the French occupation army disregarded local health regulations, exacerbating the crisis.[4] Reports in Greek newspapers claimed that the French troops had encountered suspected cases of cholera during their voyage to Greece but chose not to inform the authorities upon their arrival. Some accounts even alleged that French soldiers disposed of their dead overboard during the journey. [5]

Once in Piraeus, the French forces failed to implement any measures to prevent the spread of the disease. Infected soldiers moved freely through the city, and burials were conducted in secret during the night.[6] Weeks passed before the Greek authorities and the general population were made aware of the outbreak, delaying the response. By the time local officials began to act, cholera had spread widely, leaving the authorities scrambling to contain it. [7]

The measures eventually introduced by the Greek authorities included quarantining infected individuals and those displaying symptoms, issuing public health guidelines on hygiene and diet, and establishing healthcare centers in various locations to treat the sick. Urban sanitation efforts were ramped up, with authorities cleaning streets, removing waste, and managing the disposal of dead bodies. However, these interventions were hindered by several factors. Greece’s public health infrastructure was rudimentary at best, with limited resources, knowledge, and experience to handle such a large-scale crisis. The inadequate waste management and sewage systems in both Piraeus and Athens contaminated drinking water supplies, further facilitating the spread of the disease. Access to safe drinking water was scarce, forcing many residents to rely on contaminated sources.[8]

Overcrowding in both cities, coupled with high population density, provided fertile ground for the rapid transmission of cholera. Fear and panic gripped the population, leading many to flee the urban centers in hopes of escaping the disease. This exodus, however, spread cholera to other regions, compounding the crisis. Poverty, poor living conditions, and low levels of health literacy meant that many residents were unable to follow the public health advice issued by the authorities. Moreover, inconsistencies in the enforcement of containment measures undermined their effectiveness. Notably, movement restrictions were not applied to the occupying forces, who continued to move freely despite being the primary source of infection.[9]

The cholera outbreak highlighted the vulnerabilities of the Greek state’s infrastructure. Local authorities were unprepared to deal with a public health emergency of this magnitude, lacking both the administrative capacity and the material resources required for an effective response. The delay in addressing the outbreak, combined with the lack of coordination between the occupation forces and the Greek authorities, further exacerbated the situation. By November 1854, the outbreak had been brought under control, but not before it left a tragic toll: over 3,000 people in Piraeus and Athens had lost their lives, with hundreds of fatalities reported among the French and British troops as well. The crisis served as a sobering reminder of the devastating consequences of unpreparedness and neglect, both at the local and international levels.

Notes

[1] R. Clogg, A Concise History of Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 46-97.

[2] C. Badem, The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856) (Leiden: Brill, 2010), pp. 67-68.

[3] E. Poulakou-Rebelakou et al., “The Foreigner of 1854”, Ιατρικά Χρονικά Βορειοδυτικής Ελλάδας – Τόμος 14ος – Τεύχος 1ο (Athens: 2019), pp. 94-95.

[4] N. Δραγούμης, Ιστορικαί αναμνήσεις [Historical memories]. Εκ του Τυπογραφείου Χ. Ν. Φιλαδελφέως (Athens: 1879), p. 238.

[5] Αιών[Century], 7 July 1854.

[6] M. Κορασίδου, Όταν η Αρρώστια Απειλεί. Επιτήρηση και έλεγχος της υγείας του πληθυσμού στην Ελλάδα του 19ου αιώνα (When Illness Threatens. Surveillance and the Control of Population Health in nineteenth-century Greece], (Athens, 2002), p. 104.

[7] Αθηνά [Minerva], July 5, 1854.

[8] Government Gazette, 10 July 1854.

[9] N. Δραγούμη, Ιστορικαί αναμνήσεις [Historical memories]. Τόμος 1. Εκ του Τυπογραφείου Χ. Ν. Φιλαδελφέως (Athens, 1925), pp. 196-198; A. Παπαδοπούλου, Το Αμαλίειον Ορφανοτροφείον Κορασίδων επί τη Εκατονταετηρίδι του (1855-1954) [The Amalia Orphanage for Girls on its Centenary (1855-1954)] (Athens, 1954), pp. 7-9; X. Λούκος, “Επιδημία και Κοινωνία. Η χολέρα στην Ερμούπολη της Σύρου (1854)” [Epidemics and Society. Cholera in Ermoupolis, Syros (1854)]. Μνήμων 14 (1992): 49–69; M. Κορασίδου, Ibid., pp. 110-116; K. Κόμης, Χολέρα και Λοιμοκαθαρτήρια (19ος – 20ός αιώνας). Το παράδειγμα της Σαμιοπούλας [Cholera and Purgatory (19th – 20th century). The example of Samiopoula] (Athens, 2005), p. 55; Z. Παρασκευή, Το αρχιτεκτονικό και αστικό αποτύπωμα της πανδημίας της χολέρας (1854-1856) στην Αθήνα και τον Πειραιά [The architectural and urban imprint of the Cholera pandemic (1854-1856) in Athens and Piraeus](Athens, 2022), pp. 10-16.

COLOUR IMAGE: COURTESY ANNA BATZELI.

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.