Barış Çelik takes stock of his new undergraduate module on “The Making of the Modern Middle East”, which seeks to de-essentialise the region in students’ minds.

Barıș teaches at the School of Sociological Studies, Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield.

This semester I had the privilege of leading a second-year module entitled “The Making of the Modern Middle East”, taught at the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield. As the final assignments and the end of semester are getting closer, it is a good time to reflect on my journey with the students. This has been a journey that aimed to move beyond simplistic academic and political narratives about the Middle East, and engage with its multifaceted, dynamic realities.

One of my primary goals from the outset was to actively de-essentialise the Middle East. All too often, popular discourse and even some academic approaches portray the region as if there is something inherently flawed in its “essence”: the Middle East is underdeveloped, perpetually authoritarian, or intrinsically “backward” because of how it essentially is. Most of the students reported being exposed to this depiction of the Middle East – be it in their secondary school education, in the news or through popular culture. Others mentioned that they knew very little of the region due to lack of interest or the absence of the Middle East from the UK school curriculum. The students also reported not having much historical knowledge of the Middle East.

It was therefore important to not only provide students with critical explanations on various key events in the Middle East, but also to help them understand what these events were in the first place. To help students develop this baseline understanding, I did not want to rely too much on conventional textbooks on Middle East politics, as I find many of them have an either overly chronological or overly thematic focus. Therefore, each week I included both “contextual readings” in which key events, people, and places were outlined, as well as “explaining/understanding readings” where these events were interpreted through the lens of a concept, such as Orientalism, historicism, colonialism or modernity.

The aim was to foster a nuanced understanding, acknowledging both the region’s brilliance and its challenges.

In de-essentialising the Middle East, we also tried to avoid painting an overly rosy, romanticized picture of the region. It was crucial to acknowledge the struggles of the people in the region. To this end, we not only examined case studies of popular movements and everyday acts of resistance, but also the alternatives that the people of the Middle East provided to the conventional methods of governance. This helped students understand how individuals and communities in the Middle East made sense of the turbulent politics surrounding them, how they navigated the opportunities and constraints of their time, and how they actively resisted various forms of oppression and injustice. The aim was to foster a nuanced understanding, acknowledging both the region’s brilliance and its challenges.

A significant portion of the module was dedicated to understanding the cultural and social history of the late- and post-Ottoman Empire. We explored how the Ottoman state interacted with its diverse provinces in the Middle East – the varying degrees of autonomy, the systems of governance, the social hierarchies, and the economic relationships. Understanding this imperial legacy, including its uneven and enduring impact on borders, identities, and political structures, proved to be a key for students in unlocking many –but not all– of the complexities of the twentieth-century Middle East.

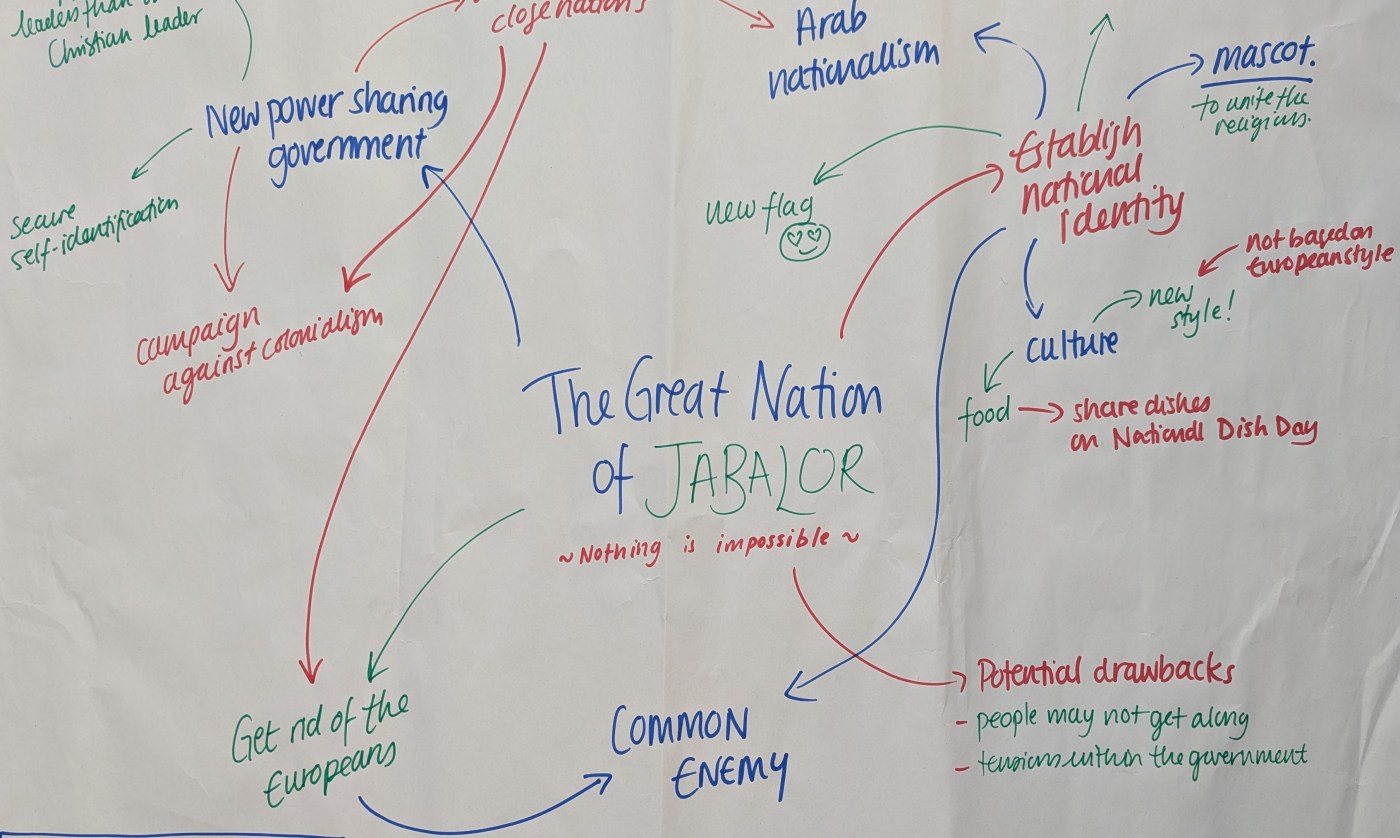

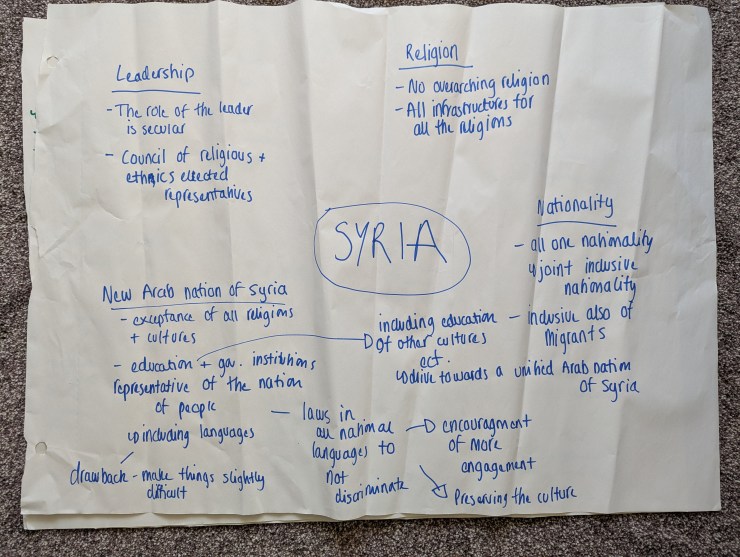

The module also aimed to challenge students’ preconceived notions of some of the key concepts that are often used with reference to their European/Western manifestations, such as nationalism, secularism, modernity, feminism, and capitalism. In a seminar activity, I gave the students the task of forming an imaginary new, independent state (which they named “Jabalor”) in the Middle East in the aftermath of the Ottoman state’s collapse. They were specifically asked to navigate the questions of nationalism (who is to be a part of the new nation) and secularism (what role to give to religion in politics). This exercise helped students acknowledge that these concepts operated in the Middle East quite differently from their Western European or North American trajectories.

Navigating “Israel-Palestine” in the classroom was particularly challenging. We started tacking this topic by tracing its historical roots, exploring the late Ottoman period, the impact of colonialism, the discourses around modernity, the mandate system, and the rise of competing nationalisms. Crucially, we aimed to connect key early developments such as the Ottoman land reforms, Jewish migration to Palestine, different discourses around Zionism, and the rise of Arab nationalism to broader themes explored throughout the module, such as modernity, colonialism, nationalist movements, as well as the environment.

Throughout the semester, we have been reflecting on the very title of our module, “The Making of the Modern Middle East”, by consistently questioning each of its constituent parts. What exactly do we mean by “Middle East”? To what extent are we limited by the colonialist understanding when we still use this term? Similarly, the notion of being “made” prompted us to consider the various actors and forces – both internal and external – that have shaped the region’s trajectory. We have also seen that the concept of “modern” is far from straightforward, not least because it was experienced and interpreted differently across the region.

The thoughtfulness and self-awareness evident in their journal assignments underscored the power of such self-reflective practices in fostering a more meaningful engagement with the weekly topics.

Inspired by a colleague’s insightful advice, I used a self-reflective journal assignment. This assignment made up 40% of the overall mark from the module, with a conventional essay assignment making up the rest. In the journal students were asked to reflect upon their own engagement with a reading, seminar exercise, or lecture. This has pushed students out of their comfort zone of writing analytical essays, where they normally examine a theory or event critically. Instead, in their journal the students were expected to actively engage with the material on a personal level, tracing the evolution of their understanding, identifying moments of intellectual challenge and growth, and articulating how their perspectives on the Middle East had shifted. The thoughtfulness and self-awareness evident in their assignments underscored the power of such self-reflective practices in fostering a more meaningful engagement with the weekly topics.

Witnessing students grapple with Middle East politics, challenge their own assumptions, and develop a more nuanced understanding of the region as an outcome has been truly inspiring and rewarding for me. I hope that the students leave the module not with a set of definitive answers, but with a toolkit for thoughtful engagement with the Middle East that will help them recognise diverse perspectives around the region.

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.