Ümit Kurt reflects on one of the leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, Cemal Pasha, and his ambivalent relationship with Ottoman Armenians.

Ümit is Lecturer and DECRA Fellow at the University of Newcastle, Australia

Falih Rıfkı (Atay)’s memoirs of his time as Cemal Pasha’s adjutant in Sinai open with a scene in which the pasha dresses down the Arab gentry of Nablus in his office. Cemal begins by scolding them for their alleged nationalist activities before exhibiting his merciful side, ordering that their punishment be limited to Anatolian exile.[1] The scene gives us a glimpse of how the third most powerful figure in the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) regime wielded power: while Cemal firmly believed in modernization and civilization, he was also an advocate of ruthless discipline. For Falih Rıfkı his mannerisms were reminiscent of European colonialists.

As military commander and governor in Greater Syria Cemal implemented a slew of harsh, totalitarian policies in the name of “civilization”, targeting particular ethnic groups. He legitimized these actions through the construction of an ideal Ottomanist identity and citizenship; arbitrary experiments in social engineering of Arabs, Armenians, and even Jews in Syria were justified by a quasi-colonialist raison d’etat.

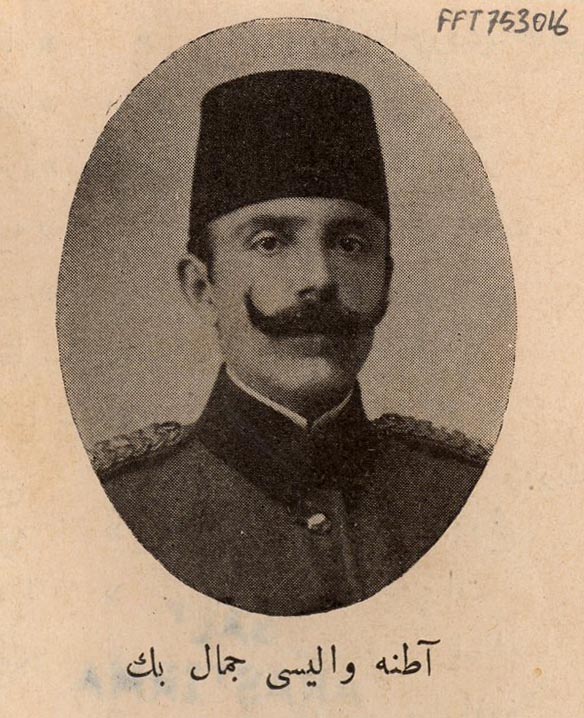

SOURCE: SALT GALATA ARCHIVES, ISTANBUL

In contrast to his well-known murderous oppression of Arabs, Cemal’s stance towards Armenians has proved harder to pin down. I hold that his conduct towards the ethnic groups in Greater Syria – beginning with Arabs, Armenians, and Jews —aimed at making them incapable of harming the sovereignty, unity, and authority of the Ottoman state. To this end, he went to great lengths to ensure that the Armenian population would not constitute a majority in any of the regions to which they were deported, nor be in a position to make claims that might pose a threat to the sovereignty of the Ottoman state. Cemal Pasha considered the Armenians’ demands for reform, and the opportunity they offered the European Powers to put pressure on the Ottoman government as a stain on the honour of the Empire. He thus held the same view as Talat and Enver: that such a threat and the “trouble” it encouraged should be eliminated – completely.[2] As Cemal Pasha put it, “The Armenian uprisings [sic] are events that place the existence of the state in danger.”[3]

Notwithstanding all this, Cemal maintained good relations with the Armenian congregation’s leaders and leading members of this community throughout his career as a statesman. During his time as the Governor of Adana (August 1909), he played an active role in the trial and punishment of those involved in the mass killing of Armenians that had occurred in the province that spring.

The fundamental difference between Cemal and the other two leaders of the CUP, Talât and Enver, was the methods he wanted to employ to reduce Armenian numbers to a level that would no longer pose a threat to the Ottoman state. Cemal Pasha was a disciplinarian assimilationist, not a proponent of extermination. His aim was to Turkify and Islamise the Armenians systematically. Hence, he did not permit mass extermination in the provinces, townships, and administrative authorities (mutasarrıflık) under the command of his Fourth Army. He did, however, endeavour to make the Armenians abandon their nationality through conversion to Islam, which would serve to “thin” the numbers of those identifying as Armenians. In order to realize this goal, he aimed his conversion and assimilation policies at widows, orphaned boys, and girls under twelve. He encouraged the marriage of Armenian widows to Muslims; established orphanages for boys and girls where the speaking of any language other than Turkish was banned; and ordered Turkish families to adopt Armenian orphans, and inculcate in them Turkish morals and culture.

SOURCE: ATATÜRK KİTAPLIĞI, ISTANBUL

In his memoirs, Talât, who was in Syria at the time, noted that Cemal had no connection to “the migration of the Armenians.”[4] Cemal treated the Armenians sent to his region well, for which he received the thanks of the Armenian community. In their deliberate cruelty, Talât and his supporters within the CUP do seem the opposite of Cemal, who hoped to limit the deportees’ suffering as much as was feasible. Yet in principle, Cemal supported the deportations and stood firmly behind the decision that all of the deportations mandated between February and May 1915 were necessary.

As Salim Tamari eloquently notes, World War I obliterated four centuries of a rich and complex Ottoman patrimony, replacing it with

what was known in Arabic discourse as ‘the days of the Turks’: four miserable years of tyranny symbolized by the military dictatorship of Ahmad Cemal Pasha in Syria, seferberlik (forced conscription and excile), and the collective hanging of Arab patriots in Beirut’s Burj Square on 15 August 1916. [5]

He maintains that Ottoman constitutional reform was unable to create a multiethnic domain that included Syria-Palestine as an integral part of the empire.[6] Such hopes collapsed under the burdens of war and the dictatorial regime of Cemal. As a twentieth-century nationalist, Cemal firmly believed that his sacred duty was to rescue Ottoman lands from decades of British “encroachment,” a cause worth any sacrifice, including that of “filling the Suez Canal with the corpses of [he] and [his] friends” if he failed.

After the resignation of Talât Pasha’s cabinet on 8 October 1918, Cemal fled with seven other CUP leaders to Germany, and then Switzerland. Tried in absentia for war crimes by a military tribunal in Istanbul, he was found guilty in July 1919 and sentenced to death. He actively supported the Kemalist-nationalist movement in Anatolia, recognized Mustafa Kemal’s leadership in Ankara, and had close relations with him until 1921-22. Cemal served the Kemalist government as liaison officer in negotiations between Ankara and Russia’s new Communist regime. It was in that capacity that in the summer of 1922 he travelled to Tbilisi, where on 21 July he was killed by Armenian assassins: revenge for his role in the destruction of their people.

Notes

[1] Falih Rıfkı Atay, Zeytindağı (Istanbul: Pozitif Yayınları, 2004), 17.

[2] Cemal Paşa, Hatırat (Istanbul: Arma Yayınları, 1996), 371.

[3] Quoted in Enver Ziya Karal, Osmanlı Tarihi, Vol. IX (Ankara: TTK Yayınları, 1996), 452.

[4] Talat Paşa’nın Anıları, prepared by Alpay Kabacalı (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Yayınları, 2011), 130.

[5] Salim Tamari, Year of the Locust: A Soldier’s Diary and the Erasure of Palestine’s Ottoman Past (CA: University of California Press, 2011), 5.

[6] Ibid., 3.

FEATURE IMAGE: CEMAL PASHA (FOURTH FROM LEFT), SOURCE: ZAFER TOPRAK ARCHIVES